A text by Can Kantarcı on the book

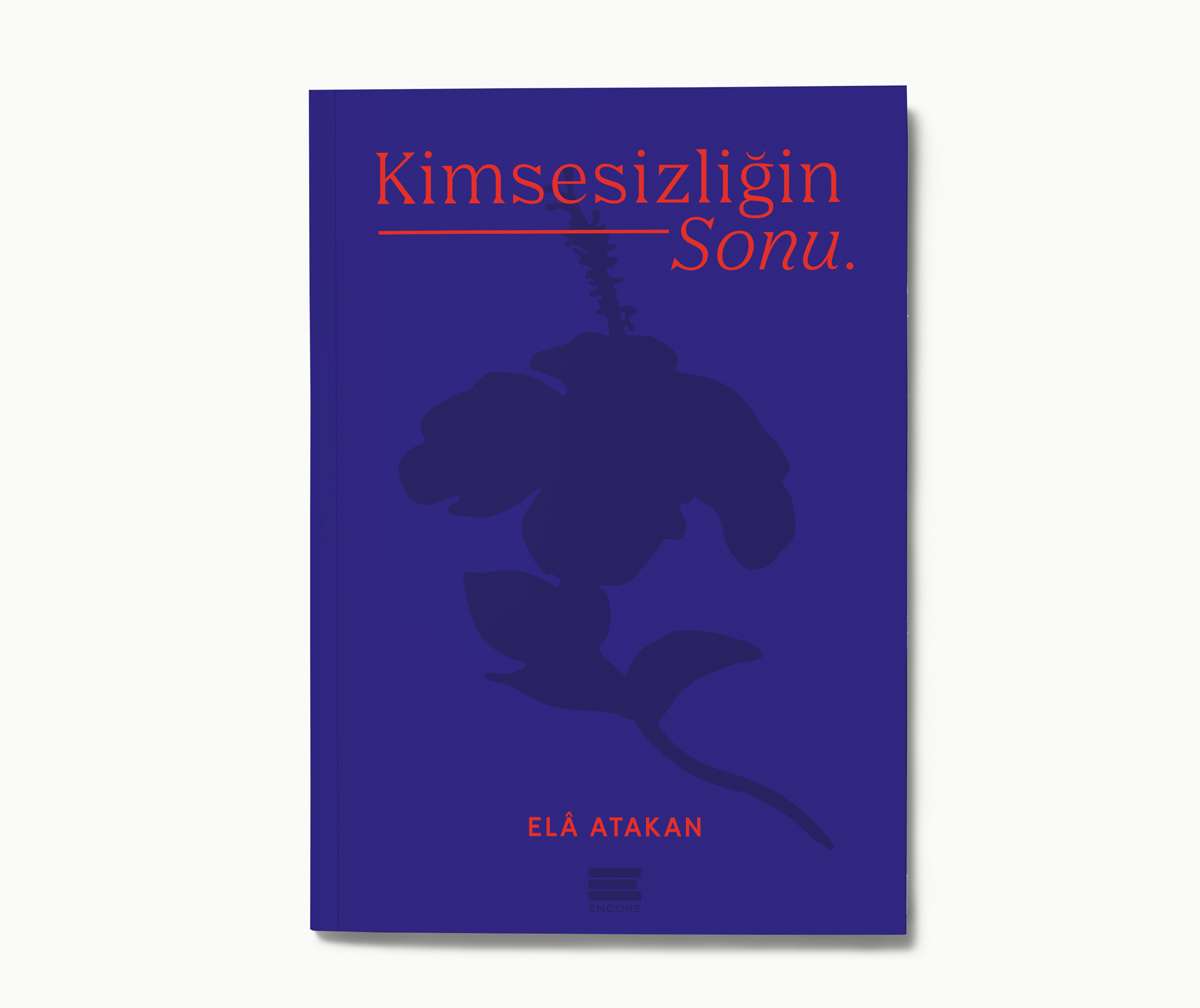

The End of Solitude by Elâ Atakan

“I find myself in a moment I might call the daylight of night,” begins a chapter in The End of Solitude. If you have reached this point, it means you have already taken your seat in a quiet corner of this singular book’s singular world. Someone is recounting their story or rather, their stories lived through different nights of different days. Who is this person? Nobody. Or better: it doesn’t matter who they are. What matters now is not to forget that they are searching for an ending.

But what is being told here? Or rather, what is being remembered by both us and the narrator? First and foremost, we are reminded what literature is for. Beyond simply narrating a story, this book demonstrates how the specific gravity of carefully chosen words, rather than casually uttered ones, can lift unseen burdens. It reminds us that it’s not just what is told, but how the calm, almost tranquil manner of its telling that carries weight. And, with the gentlest of touches, it reminds us through the voice of a Nobody who has once spoken long and deeply with herself, and learned from it of the futility of saying too much in the hope of meaning more.

In this delicate gathering of prose and poetic fragments, which offer much to anyone willing to listen, familiar themes like love, family, friendship, and affection are handled in unfamiliar ways with in a self-contained, intimate cosmos. The Nobody who speaks of these things

knows that what she touches belongs first to herself, and that she has nothing to share unless she chooses to. It is precisely because of this detachment that she handles them with such clarity, such quiet passion owing nothing to anyone but herself.

As The End of Solitude draws to a close, the Nobody whose presence we’ve grown used to within the layered time of the book says: “You cannot see what I hold in my hands now,” in the daylight of night. And we, the readers, who feel we’ve dwelled for centuries in the world this book has built, do not want her to go. We want her to keep speaking. to keep telling us what she holds. because we know, from everything we’ve read so far, that she is a narrator who never enchants us into forgetting ourselves, nor imposes her voice over ours. All she asks is to help us see the familiar a new and invites us, now part of her singular world, to do the same.

“Gecenin gündüzü diye adlandırabileceğim bir kesitteyim” diye açılır Kimsesizliğin Sonu’nda bir bölüm. Bu bölüme geldiyseniz, bu kendine has kitabın kendine has evreninde bir köşeye çoktan geçip oturmuşsunuz demektir. Birisi size, farklı gecelerinin farklı gündüzlerinde yaşadığı hikâyesini, hikâyelerini anlatmaktadır. Kimdir bu? Kimse’dir. Ya da şöyle diyelim: kimse olması önemli değildir. Ancak sonunu aramakta olduğunu unutmamamız, bu aşamada, yeterlidir.

Ne anlatır peki? Ya da ne hatırlatır mı demeli, hem bize hem de kendisine? Öncelikle, edebiyatın ne için olduğunu anlatır. Salt hikâye aktarmaktan öte, gelişigüzel laflar yerine özenle seçtiğimiz kelimelerin özgül ağırlıklarının bir araya gelerek ne gibi yükleri hafifletebileceğini hatırlatır. Hikâyenin aktarımından ziyade, ya da onunla birlikte, o hikâyenin dingin ve huzur bulmaya yakın bir üslupla aktarımının da ne kadar önemli olduğunu hatırlatır. Ve elbette, çok konuşarak çok şey anlatmanın beyhudeliğini, vakti zamanında kendiyle çok konuşarak ve bu konuşmalardan dersler çıkararak anlamış bir Kimse’nin bu metni, bize bunu da, incecik yapısıyla, nezaketle hatırlatır.

Kimselere hatırlatacağı çok şey olan bu nesir ve şiir parçacıklarından oluşan metinlerde; aşk, aile, dostluk, sevgi gibi üzerine bir şeyler okumaya (ve hatta yazmaya) çok alışık olduğumuz konuların, kurulan kendine has evrende bambaşka biçimlerde kendilerini ele aldırdıklarını göreceksiniz. Her kimse ele alan, dokunduğu şeylerin öncelikle kendilerine ait olduklarının, başka kimseye zorunda olmadıkça anlatacakları bir şeyleri olmadığının son derece farkında. Tam da bu yüzden, ele alınmaya izin veren konular, ona bu kadar berrak, duru ve tutkulu bir hâlde bırakmışlar kendilerini. Başka kimseyi düşünmeden, kimseye de bir borç hissetmeden – kendilerinden başka.

Kimsesizliğin Sonu’nun sonlarına yaklaşırken, “Şimdi elimde tuttuklarımı göremezsin,” der, artık varlığına çoktan alıştığımız, okuyucu olarak metnin kademe kademe tesis ettiği o farklı vakitte, “gecenin gündüzünde” yanımızdan ayrılmasını istemediğimiz bir Kimse. Biz, kitabın kurduğu evrende sanki yüzyıllardır yaşayagelen okuyucular, görmek de istemeyiz sanki. Her Kimse bu anlatıcı, elinde tuttuklarını anlatsın isteriz bize, o ana dek olduğu gibi. Çünkü biliriz ki, daha önce duyduklarımızdan, okuduklarımızdan başka, onların büyüsüne kapılmadan, kendi söyleyecek sözünü bize dikte etmeden anlatan bir anlatıcı vardır karşımızda. Tek istediği, alışılagelenleri yeni bir gözle hatırlamak ve bizim de, parçası kıldığı kendine has evrende, hatırlamamızı sağlamaktır.