exhibition

Curated by Ela Atakan, Ayça Telgeren‘s ‘Under My Skin’ turns inward to explore the memory of touch and the emotional traces left on the body. Moving away from dreamlike narratives, she focuses on skin as both a boundary and a space of connection. Through cut-out hands from old family photos, braided hair forms, and sculptural installations, she weaves a delicate language of intimacy, loss, and remembrance. The works invite us to sense what remains under the surface moments of care, gestures of affection, and the invisible weight of contact.

concrete, 30 x 110 x 66 cm

news about

Curatorial Statement

‘’The body is outside me, because it can be exposed to the effects of the world and be visible to others, because I can abstract myself from it, if to a certain degree. But on the other hand, it is the closest thing to myself, at the heart of intimacy: It touches me most deeply, it touches me at ‘my skin’. The body is that which belongs both the most and the least to me.’’1

“Contact” forms the symbolic framework of the exhibition Under My Skin.

Every body part and element in the exhibition touches the others, intertwined in an embrace. The hand and the skin are prominent in the philosophy of the touch. The skin is the geography of touching, and the hand is the most relevant body part for the act. We begin to learn and feel with our hands. Often, we perceive what we discover with our hands as if it were our entire body. Abidin Dino makes the following remarks about his drawings of hands: “The fingers on the paper became detached from anatomical logic and swarmed by themselves. They were autonomous, the fingers were self-ordained, they could twist and bend on the empty paper snuggling up as they wished, like a tughra”2. We can say the exact opposite for Telgeren’s hands. Far from being autonomous, they are hands that almost seem to exist for the other hands they touch, that touch each other with compassion; hands whose lines intermingle, which tell of the accretion of the past, of moments. These hands take refuge in one another, without intending at all to describe the character of the person they belong to as in Dino’s case, and get lost in the warmth of that moment.

With this exhibition, the artist invites us to remember with hands. In the work titled Corpus of Memory, Telgeren shows us only the hands of anonymized family members cut out of family photos at their moments of touching each other. We can identify certain hands as belonging to a baby, and others as women’s or men’s hands, but what matters is the uniqueness and ephemerality of the moment. All the hands touch each other, making a map of the most precious memories of the artist. The art of memory is formed through imaginary spaces3. And here, Telgeren creates an imaginary geography of remembering, into which we can place our own memories, our own history. Two pairs of hands that differ from the paper cutouts stand out in the exhibition. In Eternal, the artist embroiders the figure of two hands holding each other, a love that will remain for eternity, on a pillowcase with the technique of hair embroidery, an ancient tradition.

In all civilizations of the past, hair has great significance for the expression of identity. People have left various kinds of markings on bodies to designate the boundaries of its identity: Tattoos, body painting and mutilation, ornaments, ethnic garments, etc.4 All these elements are used to delimit the other and express oneself.

The use of hair is among such signs used in societies since the earliest civilizations. Hair has particular importance in Telgeren’s life and work. In her previous exhibitions, we encounter the character Mireille. In her childhood, Telgeren’s hair was cut short by her family against her will. The artist identifies this situation with Mireille, an imaginary character of her creation with short bob-cut hair and introduces her in her work as the main character. The deprivation of a visible part of the body has been perceived as a symbol of dishonor by societies of the past. “Mutilar”, the origin of the word “mutiler”, which means “to injure”, used to denote the cutting of hair in the early 16th century.

In the Byzantine period, women who raised a hand against people other than their sons were punished by cutting their hair.5 In Turkish mythology, having long, black hair is the symbol of power and beauty. The deliberate cutting of hair, on the other hand, is symbolic of mourning. In past Turkish traditions, women’s braided hair carries multiple meanings. A single braid and multiple braid bear different connotations; here, Hair has particular importance in Telgeren’s life and work. In her previous exhibitions, we encounter the character Mireille. In her childhood, Telgeren’s hair was cut short by her family against her will. The artist identifies this situation with Mireille, an imaginary character of her creation with short bob-cut hair and introduces her in her work as the main character. The deprivation of a visible part of the body has been perceived as a symbol of dishonor by societies of the past. “Mutilar”, the origin of the word “mutiler”, which means “to injure”, used to denote the cutting of hair in the early 16th century. In the Byzantine period, women who raised a hand against people other than their sons were punished by cutting their hair.5 In Turkish mythology, having long, black hair is the symbol of power and beauty. The deliberate cutting of hair, on the other hand, is symbolic of mourning. In past Turkish traditions, women’s braided hair carries multiple meanings. A single braid and multiple braid bear different connotations; here, hair, as the bearer of such cultural signs as being or not being married and having recently given birth, helps the body be deciphered without words6. In this exhibition, Telgeren’s monumental strands of hair, long, braided and black, are no longer parts of a body, and instead speak with an alphabet of their own. In this exhibition, the artist was inspired by George Bataille’s Story of the Eye, published in 1928, which tells the narrator and Simone’s erotic adventures. Starting off like a simple game, this erotic adventure explores the boundlessness of morality, touching all aspects of evil with a language that simplifies it and renders it ordinary.

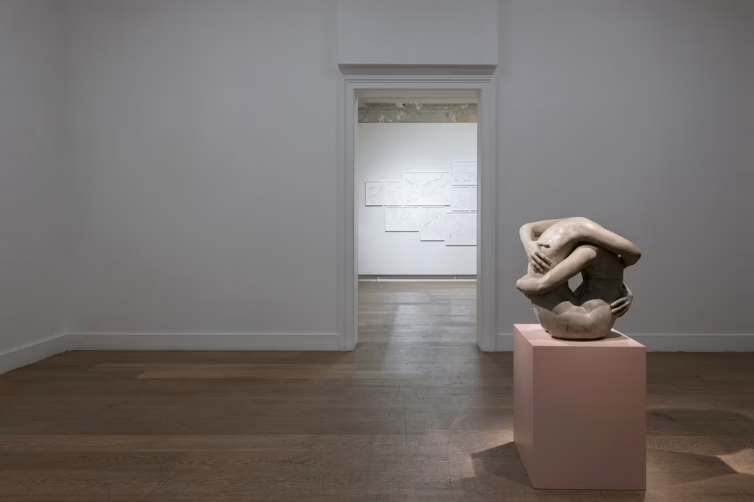

The two main characters in the story live for the pleasures of their bodies; this desire is strong enough to also affect the groups of people around them. Telgeren remarks that this story has influenced her in two ways, the first being how the boundaries of the bodies of others in the story disappear and the skins exist with their touching of each other, turning into a single body, an island of pleasure that has a life of its own. We can see a reflection of this notion in Telgeren’s work titled The Last Day of Spring, where two separate intertwined bodies turn into a single body, and in the series titled Islands, painted with acrylic on canvas. The second aspect of influence is Bataille’s inquiry into the concepts of morality and evil in the story. The artist remarks that “Bataille’s outlook on immorality, his relation with evil, rests deep in the essence of humanity”, and touches on how “the duality of morality and evil are constantly intertwined so as to both affirm and nullify one another”. These are the notions that underlie Telgeren’s sculpture Vague in this exhibition, regarding which the artist remarks on double meanings: “An entity may need to be embraced both threateningly and like a baby. With an appearance cold as concrete, yet light like a bird, it can create a sense of compassion and touch. The perception of the work can change with regard to whether one stands in front of or behind the trigger, or the sculpture can be read like a hand hanging in the air, away from all these thoughts.”7 Vague is the only work in this exhibition that stands on its own. The work can symbolize this intellectual inquiry and conflict thanks to its solitude, in contrast with the rest of the works.

In the sculptures titled The First Day of Spring and The Last Day of Spring, when we study each hand in Corpus of Memory, in the places where the strands of the Hair series touch each other and are braided together, we witness that the touch that occurs bears an internal tension in which duality, and at times multitude is embodied. This is what constitutes the power of painting and sculpture8. That moment of contact, as in real life, is the meeting point and the concentration of a clash in a single space.

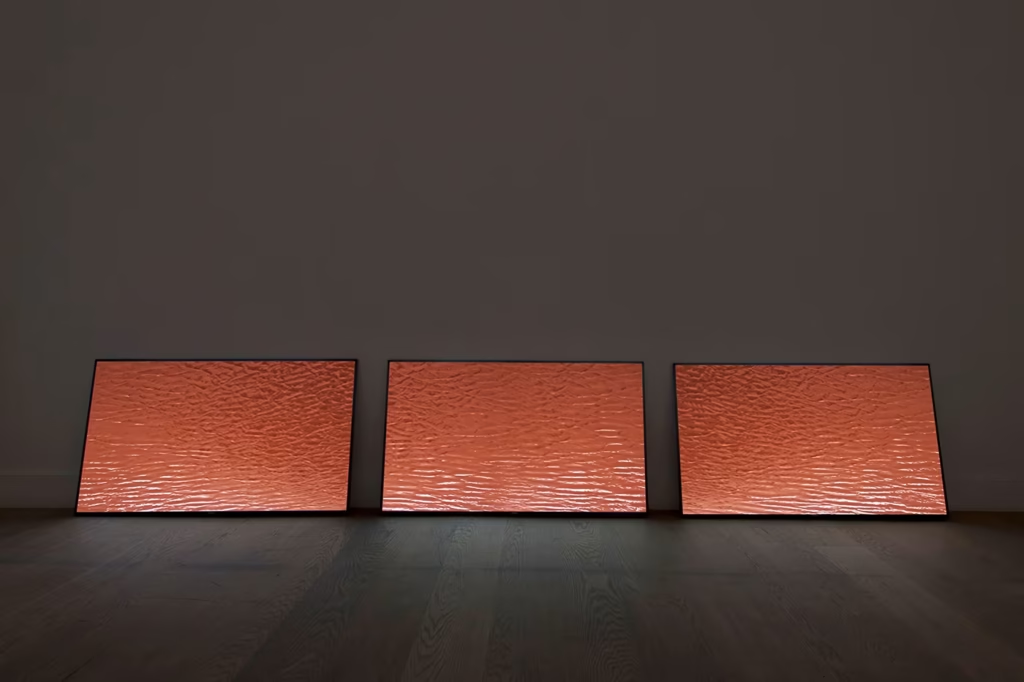

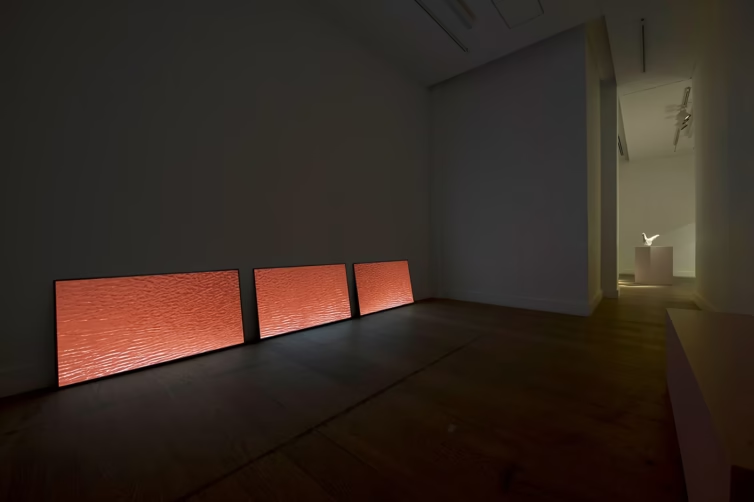

It is the skin that bears the history of the touch. The skin and the hair remember these moments of intense contact. Our skin shivers when we recall our memories back into our minds. The traces of those moments in the past reverberate in the geography of our bodies once again. In the video installation titled Under My Skin, Telgeren creates a space where the intensity of moments of clashing, touch and embrace is muted. Puddles of rain flow like the remembering of the skin. In his book The Visible and the Invisible, Maurice Merleau-Ponty remarks on the relationship of the skin with time: “The past and present are Ineinander, each enveloping-enveloped— and that itself is the flesh.”9 From the touch of our mother which we carry from our birth to our present, to the touch of a lover, from our hair being caressed to a warm embrace, the skin of others touching our lives intersects our own. As we remember their touch, our present body fades into the past, and even though they may be gone, their traces on our skin and their touch remains with us, throughout our lives.

With the exhibition Under My Skin, Ayça Telgeren invites us to reflect anew on everyone who has touched us, whom we are keeping in our desolate bodies, in our skins.

1 Renaud Barbaras, Vücudun Fenomenolojisinden Tenin Ontolojisine, Cogito, Sayı 88,Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2017, s.154-155.

2 Abidin Dino, Eller, Sel Yayıncılık, 2005, s. 41

3 Jan Assmann, Kültürel Bellek, Ayrıntı Yayınları, 2015, s. 68

4 Jan Assmann, Kültürel Bellek, Ayrıntı Yayınları, 2015, sf. 162-163

5 Christiane Noireau, L’esprit des Cheveux: Chevelures, poils et barbes, mythes et croyances, L’apart: L’esprit de la création, 2009, s. 218-223

6 Filiz N. Ölmez, Türk Kültüründe Saça Değin Simgesel ve Alegorik Değerlendirme, Halk Kültürü ve Araştırmalar Kurumu, 2016, s. 182.

7 Bu paragraftaki tüm alıntılar, sanatçı ile yapılan 19 Aralık 2019 tarihli görüşmedendir.

8 John Berger Ressamlığın ve Heykeltraşlığın Temeli Çizimdir makalesinde, kağıt üzerindeki çizimde, çizilen bedenin gerilim noktasına değinir. John Berger, Manzaralar, Metis Yayınları, 2019, s. 43.

9 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Le Visible et l’Invisible, suivi de notes de travail, Paris, Gallimard, 1964, s.315 aktaran Zeynep Zafer Esenyel, Merleau-Ponty Vücudun Fenomolijisiyle Zihin-Beden Dualizmi Aşılabilir mi?, Cogito sayı:88, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2017, s. 120.

‘’Vücut dışımdadır çünkü dünyanın etkilerine maruz kalabilir ve başkalarına görünür olabilir, çünkü bir ölçüde de olsa kendimi ondan soyutlayabilirim. Fakat bir yandan da kendimin en yakınındadır, samimiyetin kalbindedir: Bana en derinden temas eder, bana ‘tenim’de temas eder. Vücut bana aynı zamanda hem en çok ait olandır hem de en az.’’1

Ayça Telgeren, Tenden Daha Yakın sergisinde daha önceki sergilerinde odağına aldığı rüya zamanından çıkar ve bedenin, tenin belleğini sorgular. Sanatçının kağıdı işleyişi kırılgan, narin ve soyutlukta değildir artık, hafızasından çıkardığı ellerin tüm gerçekliğiyle birbirine tutunmasındadır. Hayâli karakteri Mireille’in kısa saçları, bu sergi zamanında kendi saçları gibi uzar ve serbest bırakılmış, örülmüş heykelimsi anıtlara dönüşür. Beton döküm heykeller, bedenler ve ten odası, insanı kendine, bedenine dokunma, haz alma; dokunduğu insanları hatırlama üzerine düşünmeye davet eder.

Tenden Daha Yakın sergisinin simgesel omurgasını “temas” oluşturur. Sergide her uzuv ve unsur birbirine dokunur, iç içe geçer, birbirine sarılır. Temasın felsefesine baktığımızda, el ve ten ile karşılaşırız. Ten dokunmanın coğrafyası iken, el en belirgin uzvudur. İlk ellerimizle tanır, hissederiz. Çoğu zaman ellerimizle keşfettiklerimizi tüm bedenimiz gibi algılarız. Abidin Dino, çizdiği eller için “Kağıt üstünde parmaklar anatomik mantıktan kopup özgürce kendi kendilerine istif oluveriyorlardı, özerktiler, parmaklar kendi başlarına buyruktu, diledikleri gibi sarmaş dolaş, boş kağıdın üstünde tuğra misali kıvrılıp duruyorlardı,”2 ifadesini kullanır. Telgeren’in elleri için bu anlatımın tam aksini söyleyebiliriz. Onlar özerklikten çok uzakta, adeta değdikleri diğer eller için var olan, şefkatle birbirine dokunan, çizgileri karışan, geçmişin, anların birikimini anlatan ellerdir. Bu eller, Dino’da olduğu gibi ait oldukları kişinin karakterini anlatmaya hiç yanaşmadan, birbirlerine sığınır ve o anın sıcaklığında kaybolurlar.

Sanatçı, bu sergiyle bizi ellerle hatırlamaya davet eder. Telgeren, Belleğin Gövdesi adlı eserinde, aile fotoğraflarından kadrajlanarak alınmış, kimliksizleştirilmiş aile fertlerinin sadece ellerini ve birbirlerine değme anlarını bir bütün halinde bize gösterir. Bazı ellerin küçüklüğünden dolayı bebek olduğunu, bazılarının da erkek ya da kadın olduğunu tanımlasak da, önemli olan o anın biricikliği ve uçuculuğudur. Tüm eller birbirine değer ve sanatçının en değerli hatıralarının haritasını oluşturur. Bellek sanatı, hayalî mekanlarla oluşur.3 Telgeren de burada, hayalî bir hatırlama coğrafyası yaratır; kendi hatıralarımızı, geçmişimizi oraya yerleştirebiliriz. Kağıt kesim ellerden ayrılan iki çift el, diğerlerinden ayrışır. Sanatçı, birbirini tutan iki eli, sevgiyi, kadim bir gelenek olan saç nakışıyla yastık kılıfına Sonsuz adlı eserde işler.

Saçlar, tüm geçmiş uygarlıklarda, kimliğin ifadesinde büyük bir önem taşır. Kimliğinin sınırlarını belirtmek için insanlar bedenlere farklı işaretler bırakmışlardır: Dövme şekilleri, vücudun boyanması, deformasyonları, takılar, etnik giysiler vs.4 Tüm bunlar ötekini sınırlamak ve kendini ifade etmek için kullanılır. Saçlar ve saçların kullanımı da, en eski uygarlıklardan beri toplumda bu işaretlerden biridir. Telgeren’in hayatında ve çalışmalarında saçlar büyük önem taşır. Sanatçının önceki sergilerinde Mireille karakterine rastlarız. Telgeren’in çocukluğunda saçları ailesi tarafından istemi dışında kısa kestirilmiştir. Sanatçı, bu durumu, hayâli olarak yarattığı kısa küt saçlı Mireille karakteri ile özdeşleştirir ve onu eserlerine ana karakter olarak koyar. Bedenin görünen kısımlarından birini mahrum bırakmak geçmişte toplum tarafından namussuzluk simgesi olarak algılanmıştır. Sakatlamak anlamına gelen “mutiler” kelimesinin kökü olan “mutilar”, 16. yüzyılın başlarında saçları kesmek anlamına gelmektedir. Bizans döneminde ise oğlu dışında birine el kaldıran bir kadının saçları kesilir.5 Türk mitolojisinde ise uzun ve siyah saçlı olmak, güzellik ve gücün simgesidir.

Saçın kesimi, matemi anlatır. Eski Türk geleneklerinde de, kadınların saçlarını örmesinin taşıdığı birçok anlam vardır. Tek bir örgü ile birden fazla örgünün ifade ettiği şey başkadır; saç burada evli olma ya da olmama, yeni çocuk doğurmuş olma gibi kültürel işaretlerin taşıyıcısı olarak sözle ifade edilmeden bedeni okumaya yardımcı olur.6 Telgeren’in anıtsal saçları da, bu sergide bir bedenin parçası olmaktan çıkıp, kendilerine ait bir alfabede konuşur; uzun, açık, örülü ve siyahtırlar.

Sanatçı, bu sergisinde Georges Bataille’ın 1928 yılında yayımlanan Gözün Öyküsü kitabından esinlenmiştir. Bu kitapta, anlatıcı ve Simone’un erotik maceraları anlatılır. Basit bir oyun gibi başlayan bu erotik serüven, ahlâkın sınırsızlığında dolaşarak kötülüğün tüm alanlarına onu sadeleştiren ve sıradanlaştıran bir dil ile değinir. Hikayede iki ana karakter bedenlerinin hazzı için yaşarlar; bu arzu öyle kuvvetlidir ki, etraflarındaki insan topluluklarını da etkiler. Telgeren, bu eserden etkilenmesini iki yönlü ifade eder: İlki, hikayelerdeki başkalarına ait olan bedenlerin sınırlarının kaybolması ve tenlerin temasıyla var olması, haz anında tek bir bedene, kendi başına yaşayan bir haz adasına dönüşmesidir. Bu düşüncenin izdüşümünü Telgeren’in Baharın Son Günü adlı eserinde iç içe geçmiş iki ayrı bedenin tek bir bedene dönüşmüş halinde ve tuval üzerine akrilikle resmedilmiş Adalar serisinde görebiliriz. İkincisi ise, Bataille’ın hikayede ele aldığı ahlâk ve kötülük kavramlarına açtığı sorgulamadır. Sanatçı, “Bataille’daki ahlâksızlığa bakış açısının, kötülükle ilişkisinin, insanın özünde bir yerde kurulu olduğunu” ifade eder ve bu eserin “ahlâk ve kötülüğün ikiliğinin, sürekli birbirinin içerisine geçerek hem doğrulamasına, hem de yok etmesine” değinir. Telgeren’in sergideki Muğlak heykelinin temelinde bu düşünceler vardır. Sanatçı, bu esere dair, çift anlamlılıktan bahseder: “Bir varlığın, hem tehditkâr, hem de bir bebek gibi kucaklanmaya ihtiyacı olabilir. Hem beton gibi soğuk ve ağır hem de kuş gibi hafif görüntüsüyle bir şefkat ve dokunma hissi yaratabilir. Eserin algılanması, tetiğin önünde veya arkasında durmak ile değişebilir ya da tüm bu düşüncelerin uzağında havada asılı bir el gibi okunabilir”7

Muğlak, sergideki tek tekil kalan eserdir. Eserin tüm bu fikirsel sorgulamayı ve çatışmayı simgelemesi, diğer tüm eserlerin aksine, yalnızlığından kaynaklanır. Baharın İlk Günü ve Baharın Son Günü heykellerinde; Belleğin Gövdesi eserinin her bir el parçasını incelediğimizde; Saçlar serisinin birbirine örüldüğü ve değdiği yerlerde, temasın gerçekleştiği alanlarda ikiliğin, bazen çoğulluğun vücut bulduğu bir iç gerilim taşıdığını görürüz. Bu, resim ve heykelin ağırlık noktasını oluşturur.8 O temas anı, gerçek hayatta da olduğu gibi bir çarpışmanın tek bir uzamda buluşması ve yoğunlaşmasıdır.

Dokunmanın tarihini ten taşır. Bu yoğun temas anlarını, ten anımsar, saç anımsar. Hatıralarımızı zihnimize geri çağırdığımızda, tenimiz ürperir. Tüm o anların izi, beden coğrafyamızda yeniden yankılanır. Telgeren, Tenden Daha Yakın adlı video enstalasyonunda, çarpışma, değme ve sarılma anlarının yoğunluğunun sustuğu bir alan yaratır. Yağmur suyu birikintileri, tenin anımsaması gibi akar. Maurice MerleauPonty, Görünür ve Görünmez kitabında, tenin zamanla ilişkisini anlatır: “Geçmiş ve şimdiki zaman iç içedirler her biri sarılan-sarandır ve işte ten budur.”9

Geçmişten, doğumumuzdan şimdimize taşıdığımız annemizin dokunuşundan, sevgili dokunuşuna, saçımızın okşamasından, içten bir sarılmaya hayatımıza değen başkalarının teni, tenimizde kesişir. Onların temaslarını anımsadıkça, şimdiki bedenimiz geçmişe karışır ve onlar kaybolup gitseler de, tenimizde izleri ve dokunuşları bizimle, bizim yaşamımız boyunca var olmaya devam eder.

Ayça Telgeren, Tenden Daha Yakın sergisiyle bizi tenha bedenlerimizde, tenimizde sakladığımız ve bize değmiş olan herkese dair yeniden düşünmeye davet eder.

1 Renaud Barbaras, Vücudun Fenomenolojisinden Tenin Ontolojisine, Cogito, Sayı 88,Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2017, s.154-155.

2 Abidin Dino, Eller, Sel Yayıncılık, 2005, s. 41

3 Jan Assmann, Kültürel Bellek, Ayrıntı Yayınları, 2015, s. 68

4 Jan Assmann, Kültürel Bellek, Ayrıntı Yayınları, 2015, sf. 162-163

5 Christiane Noireau, L’esprit des Cheveux: Chevelures, poils et barbes, mythes et croyances, L’apart: L’esprit de la création, 2009, s. 218-223

6 Filiz N. Ölmez, Türk Kültüründe Saça Değin Simgesel ve Alegorik Değerlendirme, Halk Kültürü ve Araştırmalar Kurumu, 2016, s. 182.

7 Bu paragraftaki tüm alıntılar, sanatçı ile yapılan 19 Aralık 2019 tarihli görüşmedendir.

8 John Berger Ressamlığın ve Heykeltraşlığın Temeli Çizimdir makalesinde, kağıt üzerindeki çizimde, çizilen bedenin gerilim noktasına değinir. John Berger, Manzaralar, Metis Yayınları, 2019, s. 43.

9 Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Le Visible et l’Invisible, suivi de notes de travail, Paris, Gallimard, 1964, s.315 aktaran Zeynep Zafer Esenyel, Merleau-Ponty Vücudun Fenomolijisiyle Zihin-Beden Dualizmi Aşılabilir mi?, Cogito sayı:88, Yapı Kredi Yayınları, 2017, s. 120.