Exhibition

Stones from the Sea brings together a group of artists who engaged with the ancient materiality of lithographic stone during seasonal residencies at Dou Print Studio. Curated by Elâ Atakan as part of the second edition of Litho Days in Turkey, the exhibition traces the timeless journey of limestone from its formation on ancient sea floors to its transformation into a printing surface that captures both geological and artistic memory.

Through layered processes of ink, touch, and time, the works explore the poetics of stone as archive, echo, and witness revealing microscopic fossils, contemporary debris, and imagined futures. The project invites a slowing down, a step outside the rhythm of the clock, and into a deep time where matter remembers more than we do.

Participating artists include: Ahmet Doğu İpek, Alessandro Rizzi, Bartłomiej Chwliczyński, Cora Texier, Selim Birsel, Burcu Yağcıoğlu, Nermin Er.

news about

Curatorial Statement

“Everything changes, nothing perishes.” OVID, metamorphoses, 8 ce*

The exhibition Stones from the Sea curated by Elâ Atakan, which opens at Ka on 24 November as part of the second edition of Dou Print Studio’s Litho Days in Turkey, takes its inspiration from the word lithos [λıθος], which means “stone” in its purest form. The origin of this word is the Ancient Greek λᾶς, which means stone from the sea. The lithographic stones, which were in the depths of the seas one hundred and fifty million years ago and are only found in certain caves and quarries around the world, are limestones that keep the traces of time of the earth. At times, albeit rarely, they contain imprints of microscopic sea creatures, crustaceans, and primitive forms of life.

Invented in 1796 in Germany by Alois Senefelder through the combination of a special limestone from the geological features of Solnhofen with ink, the technique of lithography revolutionized the art of printing in the early 19th century. In lithography, the artist executes their design under the guidance of a master printer This process consists of acidifying the drawing, letting it rest under cover, and printing it by covering the hydrophilic stone with paint. With each new work, the stone is wiped clean with sea sand or quartz, rendering it smooth and ready for the artist’s next print.

In Timefulness, geologist Marcia Bjornerud, describes her journey to the Svalbard archipelago in the Arctic Ocean to study the layers of the earth. Bjornerud relates that in the legend at the bottom of a map of global time zones, this region was marked in gray, which denotes “No Official Time”. She is fascinated by the idea that there are places which “[resist] being shackled by measures of time— no minutes or hours, wholly exempt from the tyranny of a schedule.” The technique of lithography brings together the million-year natural history of stone with the traces made by artists on the stone in each printing. It invites the artist to stay with the stone, to step out of any official measures of time. A good print requires knowledge of the stone and its reaction to ink, as well as simply waiting. In this process, the master printer, like a traveling companion, guides the artist on their journey of creation, and relates the stone to them. Each stone has unique characteristics and produces different results in each season. The color of lithography stones quarried from deeper layers tend towards gray in their hue; these stones are harder, and contain less fossils, as less life exists in these layers. Stones quarried from the upper layers are closer to the color of sand and absorb oil paints more easily. Stones quarried from different depths produce different sounds and respond differently to temperature. In order to record this process, the master printer follows the transformation of the stones over time, like a geologist conducting stratigraphy studies, and keeps stone diaries.

Ahmet Doğu İpek, Alessandro Rizzi, Cora Texier, Bartłomiej Chwilczyński, Burcu Yağcıoğlu, Nermin Er, Selim Birsel and Sibel Horada were invited to visit Dou Print Studio between June and November, as part of the second edition of Litho Days in Turkey, and produced new works in timelessness, looking from up close and far away at the history of stone, its depth in water, fossils, its metamorphosed states, and stasis.

In her lithograph titled Sea Stone Styrofoam, Sibel Horada, the first visitor of the workshop in June, was inspired by the fact that pieces of styrofoam washed ashore from the sea behave similarly to natural stones. A material Horada regularly works with, styrofoam crumbles in water, blows and scatters in the wind, just as stone turns into gravel and sand. It mixes with the elements carried in the sea and is naturally colored. For this lithograph, the artist inked the styrofoam she collected from the shores of Burgazada, and printed it on stone, picking the hues from the naturally transformed colors of the styrofoam she has found. The traces of styrofoam in Horada’s print, a material that refuses to dissolve in nature, prompt us to think about the fossils of the future. We also encounter these colors of the sea and the sky in the work of Nermin Er, who visited the workshop in summer. This time, the deep blue tone that fluctuates and expresses a variety of emotions in Er’s Pool Series appears on the path of a single stone breathing at the bottom. Horizontal scratches along this path, reminiscent of thin paper cuts, emphasize the layers of time and the deep uniqueness of the stone. The stone in the work is actualized through the inking and printing of the twine string that the artist uses in many of her works. With its borders erased, it becomes permeable, breathing upwards and towards the light.

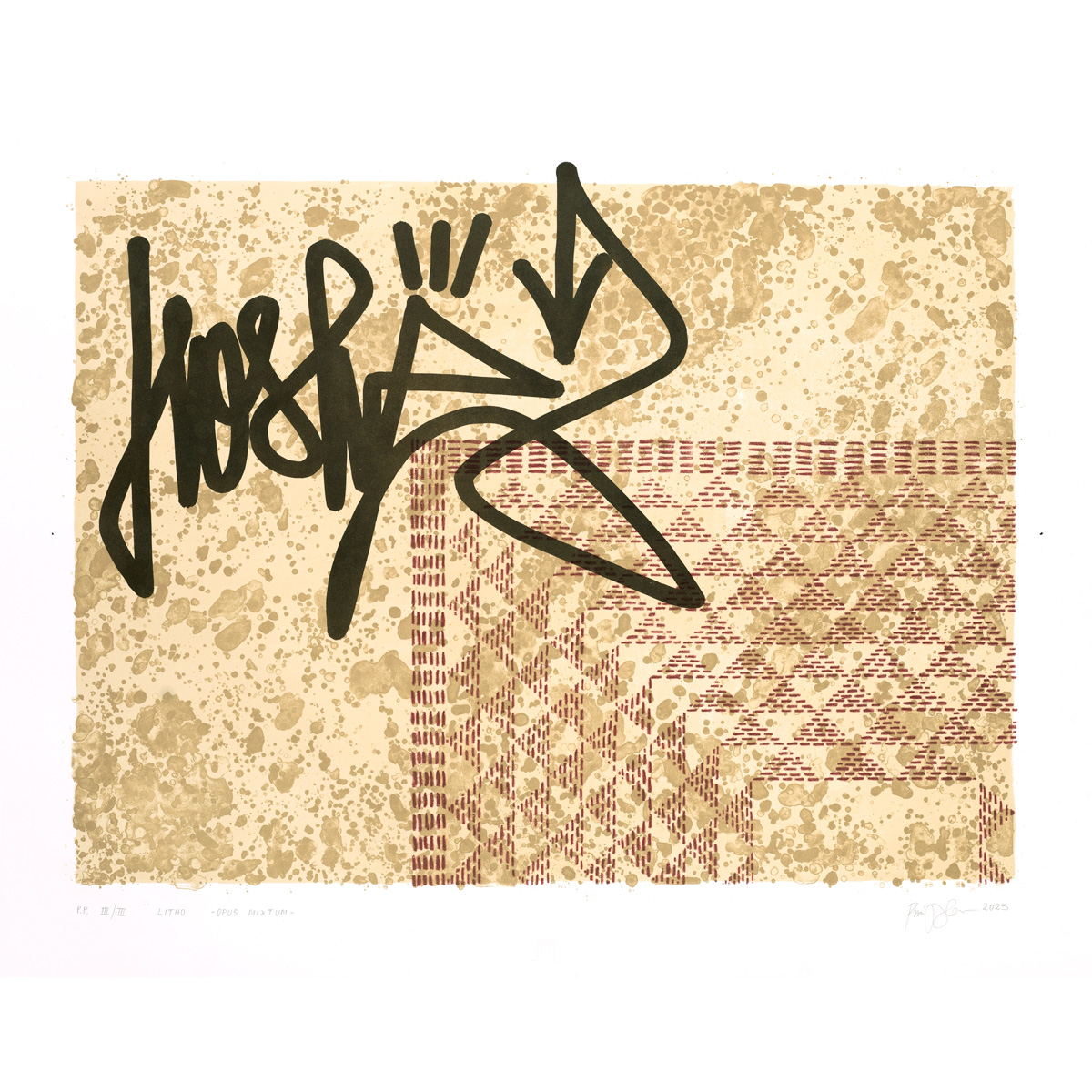

Lithographic stone is limestone. Burcu Yağcıoğlu’s CALX, which was drawn and printed in the course of three weeks, historically examines the relationship between lime, a metallic ash obtained from burning calcium and derived from the Latin word “calx” and living things. As the artist states in the accompanying text CALX, A Sketch on Lithography, Calcium and Life, “Calcium is poisonous for living things today as it was for the creatures in the early stages of evolution. Calcium in the cell means death. For living things, calcium has been internalized and transformed from an ancient waste into the skeleton, as well as shells, teeth, nails, and the shell of eggs as a protector.” The distinguishing feature of lithographic limestone is that it is devoid of traces of life to the greatest extent possible and is formed in stasis throughout millions of years. Departing from the image of Aergia, the goddess of laziness, Yağcıoğlu “imagines her as a flesh-colored stalactite of calcium, like a cave wall, and places her in the background of scattered calcium fossils and remains as a static stain”. There is an organic connection between Alessandro Rizzi’s Opus Mixtum and Yağcıoğlu’s CALX. Rizzi, too, turns to the chemistry of stone. The first layer, which the artist produced by dripping ink on the stone for two days, is based on the actual image of the limestone under the microscope. This image is identical to the image of the bones under a microscope. For the second layer of the work, the artist follows the Roman mosaic stone motifs. In the mosaics excavated from the ancient city of Zeugma, he finds similarities to those from his place of birth, and brings the two places, thousands of kilometers apart, together on a common stone. The last layer of the work connects us to the present.

The Italian artist draws his tag, which he often employs in his practice, on a stone this time, rather than on a wall. The artist’s tag is based on the word “γνῶθι σεαυτόν”, written at the entrance of the temple of Apollo in Delphi, which means “know thyself”. With this final layer, Rizzi completes a cycle, weaving the stone through time, from its material history to its cultural past, and ultimately, to the present. Bartłomiej Chwilczyński’s working practice forms around lithography. The artist has been creating works with different lithography machines in one of the oldest lithography workshops in Poland, and lecturing in this field in Krakow, as well as working with the technique of monolithography in recent years. He combines lithography with collage, pattern drawings, paper cutouts painted in various colors, using these techniques to create shadows on stone. Influenced by the art of Far Eastern calligraphy, he draws the last layer of his works with the help of a brush using oil-repellent black chroma acrylic, creating instant near-perfect traces on paper. Ankarara, the work he has produced for this project, is part of the Journey series, made with this brush method. Chwilczyński’s lithograph resembles an unfinished star, or roads as seen from the sky.

The workshop visits took place in different seasons. Just as the lithography stone changes according to temperature and humidity, the colors chosen by the artists visiting the workshop for their works have also changed naturally according to the seasons. While blue tones dominate the works of Horada and Er, who visited at the beginning of summer, the colors of sand, stone and soil became more prominent in Rizzi and Chwilczyński, along with Yağcıoğlu, whose visits were during the hotter summer months. Selim Birsel’s Mount Pelineo also carries the light of autumn, the time of his visit. The artist carves a hole in the wall and looks out from the inside. In this lithograph, Birsel looks at Mount Pelineo, the highest hill on Chios Island, near the village of Volissos. The artist follows the travel of light on this mountain at different intervals of time. In his book Ziyaret, which refers to his works between 2009-2017, Birsel writes the following note, as if describing the Mount Pelineo lithograph: ‘’In the saffron night, a shadowy window opened, in which our world was conceived…’’ The colors in this shadowy window come from a limestone belonging to the artist, which closely evokes the geological layers of the earth. In contrast with the close-up views of Yağcıoğlu and Rizzi, Birsel looks at the mountain, a monolithic stone, from a distance in this work.

Ahmet Doğu İpek’s diptych of MA-A.I and MA-A.I.06 perhaps constitute the continuation of this distant gaze, for this time, his stones are not on the earth, but reaching towards the depths of the sky. The stones on earth, bearing different Figures, have an important place in the artist’s practice. In this diptych work, we watch a meteorite dragging with it small fragments scattered by its friction and hanging in the air in absolute silence. The artist makes momentary scratches on the lithography stone. Like the splitting of the surface of black water at dusk, its echoes scatter around. These echoes do, in fact, have a sound. As the artist scatters countless dots on the stone, like meteors raining down on a planet without an atmosphere, a unique metallic rain music is created on the surface of the stone. These strokes unsettle what the stone has held in it for millions of years, reminding us of the past and the transformation of the material from which it was formed. In the making of the asteroid lithograph, which looks like glass in darkness, he applies what looks like an accidental stain on the stone and disperses it with air. The distribution of the ink on the stone creates the texture of the stone in the print. In this diptych, which is part of the Ma Series featuring stars, white paper, which the artist frequently uses in his practice, is replaced by stone. Coincidentally, Ahmet Doğu İpek’s first notebooks in his childhood were also stones.

French lithographer Cora Texier employs the lavis technique in her practice. This technique involves wetting the stone and allowing the ink to disperse randomly. Due to the use of this technique, textures play an important role in her lithographs, often becoming the expression of natural materials in stone. The remains of trees, pebbles and plants she has collected during her walks in the park near her home come to life again in her lithographs. Since 2018, Texier has hosted many artists in her lithography workshop in Châtenay-Malabry near Paris, collaborating with them in her lithographic work. The work in this exhibition is titled Ylem, which means the original matter from which the basic elements have been formed. This lithograph is inspired by the formation of chimney rocks in Cappadocia and the artist visit to the Uçhisar Castle. The artist states that these places whisper to her a single truth: the universe, the stones, the stardust, and the matter that encompasses them all. In the Uçhisar Castle, the artists noticed a naturally formed stone-shaped opening, facing the depths of the cave. This opening, photographed by Naz Önen, has guided what the artist intended to express in stone. By applying the lavis technique on the lithography stone, Texier creates an interpretation of the void, the abyss, which, according to her, denotes a transition in time, with the features reminiscent of topography that she creates through light and shadows with ink.

The exhibition Stones from the Sea is the culmination of the visits of eight artists with different experiences and art practices, each encountering the millions of years old limestone. Each artist has conveyed in their works what the stone has whispered to them during their time in the studio. Although the visual language of the works in this exhibition may vary at first glance, it deeply carries the guidance of a single stone. They were produced at completely different times of the year, by the hands of the same master printer, on the same machine, and printed on the same type of paper. The journey of limestone, once under water, in the depths of caves and rocks, has concluded in paper. The ancient time of the stone, which can perhaps never be imagined within the confines of human life, has advanced a little more, and the stone has withered a little more with the production of each artist, and the traces left by the artists are what remains.

* Marcia Bjornerud, Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World (Published in Turkish as Yeryüzünün Zamanı Bir Jeolog Gibi Düşünerek Dünyayı Kurtarabilir Miyiz?, Metis, 2020)

“Her şey değişir, hiçbir şey yok olmaz.” OVIDIUS, dönüşümler, ms8*

Dou Print Stüdyo’nun bu yıl ikincisini düzenlediği Türkiye’de Litografi Günleri kapsamında, 24 Kasım’da Ka’da açılan Denizden Çıkan Taşlar sergisi ilhamını en saf haliyle taş anlamına gelen lithos [λıθος] kelimesinin kendisinden alır. Bu kelimenin kökeni daha derinlerde Antik Yunanca’da denizden çıkan taş anlamına gelen λᾶς’a dayanır. Bundan yüz elli milyon yıl önce suyun derinliklerinde olan ve sadece dünyadaki bazı mağaralardan, taş ocaklarından çıkartılan litografi taşları, yeryüzünün zamanını tutan kireç taşlarıdır. İçlerinde nadiren de olsa küçük deniz canlılarının, kabukluların, ilkel yaşam türlerinin izlerini taşır.

1796 yılında Almanya’da Alois Senefelder’in Solnhofen jeolojik yapısından gelen özel bir kireç taşını mürekkeple buluşturmasıyla icat ettiği litografi tekniği, 19. yüzyılın başında baskı sanatında devrim yaratır. Bu teknikte, sanatçı, master printer’ın kılavuzluğunda taş ile buluşur. Bu süreç çizimin asitlenmesi, üstü örtülerek bekletilmesi ve suyu emen taşın üzerinde boya verilerek basılmasından oluşur. Her yeni işte, taş, denizden çıkan kum ya da kuartz taşıyla silinir ve sanatçıya pürüzsüz bir şekilde hazır hale getirilir.

Bir jeolog olan Marcia Bjornerud Yeryüzünün Zamanı kitabında, Arktik Okyanusu’nda Svalbard takım adalarına, yeryüzünün katmanlarını incelemek için gittiği yolculuğu anlatır. Bu bölge, haritanın altındaki sınıflandırmaya göre gri renktedir ve Resmi Zamanı Yok anlamına gelir. Araştırmacı, ‘‘zaman ölçüleriyle zincirlemeye direnmiş, dakikaların ya da saatlerin olmadığı, bir programın tahakkümünden tümüyle bağımsız yerler olduğu düşüncesiyle büyülenir.’’ Litografi tekniğini de, taşın içinde taşıdığı milyon yıllık doğal geçmişi, sanatçıların her defasında taşta bıraktıkları izlerle buluşturur. Sanatçıyı, adeta resmi zamanı olmayan bir zamandışılığa, taşta kalmaya davet eder. İyi bir baskı için taşı tanımak, mürekkebe vereceği tepkiyi bilmek ve beklemek gerekir. Bu süreçte, bir yolculuk eşlikçisi gibi master printer, sanatçının üretim yolculuğunda ona yol gösterir, taşı ona anlatır. Her taş birbirinden farklı özelliklere sahip olduğu gibi, farklı mevsimlerde farklı sonuçlar verir. Daha derinden çıkartılmış litografi taşlarının rengi kum renginden griye döner, daha sertlerdir ve o alanda daha az canlı olduğundan fosillere nadir rastlanır. Üst katmanlardan çıkartılmış taşlar ise, kum rengine yakındır ve yağlı boyaları daha kolay emerler. Ayrı derinliklerden çıkartılan taşların, sesleri de, ısıya verdikleri cevaplar da farklıdır. Tüm bunların kayıt alınması için master printer taşla bir jeoloğun stratigrafi etütleri yapması gibi zaman içerisindeki dönüşümlerini takip eder, taş günlükleri tutar.

Türkiye’de Litografi Günleri II kapsamında davetli olan sekiz sanatçı Ahmet Doğu İpek, Alessandro Rizzi, Cora Texier, Bartłomiej Chwilczyński, Burcu Yağcıoğlu, Nermin Er, Selim Birsel ve Sibel Horada Haziran- Kasım ayları arasında, Dou Print Studio’ya ziyaretler gerçekleştirdiler. Atölyenin kurucusu ve master printer’ı Doğu Gündoğdu ile kendi üretimlerinden yola çıkarak, taşın geçmişine, sudaki derinliğine, fosillere, başkalaşmış hallerine, çağrışımlarına, durağanlığına, yakından ve çok uzaktan bakarak zamandışılığın içerisinde yeni işler ürettiler.

Haziran ayında atölyenin ilk ziyaretçisi olan Sibel Horada Deniz, Taş, Strafor ismini verdiği taş baskısında, denizden kıyıya vuran strafor parçalarının doğal taşlardan farklı davranmayışından ilham alır. Horada’nın sıklıkla çalıştığı malzemelerden biri olan straforlar, bir taşın kuma, çakıla dönüşmesi gibi suda ufalanır, rüzgârda uçuşur ve saçılırlar. Denizin içindeki taşıdığı elementlerle karışır, doğal olarak boyanırlar. Sanatçı da, bu taş baskısı için, Burgazada’nın kıyılarından topladığı straforları mürekkepleyerek taşa basar ve tonlarını bulduğu straforların doğal yolla dönüşmüş renklerinden seçer. Horada’nın baskısındaki doğada asla çözülmeyen straforların izleri, bizi geleceğin fosillerine dair düşündürür. Denizin ve gökyüzünün bu renklerine yine yazın atölyeyi ziyaret eden Nermin Er’in eserinde de rastlarız. Er’in Havuz Seri’lerindeki dalgalanan ve duyguları ifade eden derin mavi tonu bu sefer, dipte nefes alan tek bir taşın yolunda belirir. Bu yol boyunca incecik kağıt kesiklerini andıran bu yatay çizikler, zamanın katmanlarını, taşın derindeki tekliğini vurgular. Eserdeki taş, sanatçının birçok çalışmasında kullandığı sicim ipini mürekkepleyerek baskısını almasıyla gerçekleşir. Sınırları silinmiş, geçirgen bir hâl alarak, ışığa, yukarıya doğru nefes alır. Litografi taşları, kireç taşlarından seçilir. Burcu Yağcıoğlu’nun çizimi ve baskısı üç hafta süren CALX eseri, kalsiyumun yakılmasından elde edilen metalik bir kül olan ve Latincede calx kelimesinden türeyen kirecin canlılarla kurduğu ilişkiyi tarihsel olarak inceler. Sanatçının esere eşlik eden CALX, Litografi, Kalsiyum ve Yaşam Üzerine Bir Taslak metninde değindiği gibi ‘‘kalsiyumun evrimin erken aşamalarındaki canlılar için olduğu gibi bugünün canlıları için de zehirlidir, hücre içinde kalsiyum ölüm anlamına gelir. Kalsiyum canlılar için kadim bir atıktan, bedenlerinin içine alınarak iskelete, kabuklara, dişlere, tırnaklara ve koruyucu olarak yumurtaların kabuğuna dönüşmüştür.’’ Litografi taşlarının diğer kireç taşlarından ayrılan özelliği, yaşam kalıntılarını olabildiğince içinde barındırmaması ve milyon yıllar boyunca durağanlığın içerisinde oluşmasıdır. Yağcıoğlu, tembellik tanrıçası Aergia imgesinden yola çıkarak ‘‘onu ten renginde bir kalsiyum sarkıtı, bir mağara duvarı’’ gibi hayal eder ve durağan bir leke olarak dağılmış kalsiyum fosillerinin, kalıntıların arka planına yerleştirir. Alessandro Rizzi’nin Opus Mixtum eseri ile Yağcıoğlu’nun CALX eseri arasında, organik bir bağ vardır. Rizzi de taşın kimyasına yönelir. İki gün boyunca taşa mürekkep damlatma tekniği ile gerçekleştirmiş olduğu ilk katmanı, kireç taşının mikroskop altındaki gerçek görüntüsünden yola çıkarak yapar. Bu görüntü bir canlının mikroskop altındaki kemik görüntüsünü andırır. Sanatçı, eserin ikinci katmanı için Roma mozaik taş motiflerinin peşinden gider. Doğduğu yerdeki mozaiklerinin benzerlerini Zeugma antik kentinden çıkarılan mozaiklerde bulur ve bu birbirinden kilometrelerce uzakta olan iki yeri ortak bir taş zeminde buluşturur. Eserin son katmanı ise bizi şimdiye bağlar. İtalyan sanatçı pratiğinde sıklıkla kullandığı tag’ini bu sefer bir duvara değil de, taşın üzerine çizer. Sanatçının tag’i, Delfi’deki Apollon tapınağının girişinde yazan kendini bil anlamına gelen γνῶθι σεαυτόν’dan gelir. Rizzi, bu son katmanla beraber, taşın zamanda, maddesel tarihinden, kültürel geçmişine ve en son da şimdiki zamana örerek bir döngüyü tamamlar.

Bartłomiej Chwilczyński’nin çalışma pratiğinde, litografi merkezdedir. Polonya’nın en eski litografi atölyelerinden birinde farklı litografi makinalarıyla üretim yapan ve Krakow’da bu alanda ders veren sanatçı son yıllarda monolitografi tekniğiyle çalışmaktadır. Taş baskıyı kolaj, desen çizimleri, farklı renklere boyanmış kesilmiş kağıtlarla, taş üzerinde gölgelemeler yaparak bir araya getirir. Uzak Doğu kaligrafi sanatından etkilenen sanatçının eserlerinin en son katmanını bir fırça yardımıyla yağ tutmayan siyah chroma akrilik kullanarak çizer ve bu sayede kağıt üzerinde anlık mükemmele yakın izler oluşturur. Litografi tekniğiyle, bu proje için ürettiği eseri Ankarara, bu fırça yöntemiyle yapıldığından serisinin bir parçasıdır. Chwilczyński’nin taş baskısı, yarım kalmış bir yıldızı ve gökyüzünden görünen yolları çağrıştırır.

Atölye ziyaretleri farklı mevsimlerde gerçekleşmiştir. Litografi taşı, sıcaklığa, neme göre değişerek baskıda nasıl farklı bir etki bırakıyorsa, atölyeye gelen sanatçıların taş baskılarında seçtiği renkler de, mevsimlere göre renk değiştirmiştir. Yazın başında ziyarete gelen Horada ve Er’de mavi tonları hakimse, yazın sıcağına doğru Yağcıoğlu’yla beraber, kumun, taşın, toprağın renkleri Rizzi ve Chwilczyński’de belirginleşmiştir. Selim Birsel’in Mount Pelineo eseri de üzerinde ziyaret ettiği zamanı sonbaharın ışığını taşır. Sanatçı, duvara bir oyuk açarak, içeriden dışarıya bakar. Selim Birsel, adını da koyduğu bu taş baskıda baktığı yer Sakız Adası’nın Volissos köyünün yakınlarında, adanın en yüksek tepesi olan Pelineo dağıdır. Sanatçı, zamanın farklı aralıklarında ışığın bu dağın üzerindeki seyahatlerini izler. 2009-2017 arasındaki eserlerine değinen Ziyaret kitabında ise adeta Mount Pelineo taş baskısını anlatırcasına şu notu düşer: ‘‘Safran gecede dünyamızın gebe olduğu belirsiz bir pencere açıldı…’’ Bu belirsiz pencerenin içerisinde yer alan renkler, yakından yeryüzünün jeolojik katmanlarını çağrıştıran sanatçıya ait bir kireç taşından gelir. Birsel, Yağcıoğlu ve Rizzi’nin yakından bakışının tam aksine, bu eserle, yekpare bir taş olan dağa uzaktan bakar.

Ahmet Doğu İpek’in MA-A.I ve MA-A.I.06 diptiği, belki de bu uzaktan bakışın devamlılığını teşkil eder, zira onun taşları bu sefer yeryüzünde değil, gökyüzünün derinliklerine doğrudur. Farklı Suretler taşıyan yeryüzündeki taşların, sanatçının pratiğinde önemli bir yeri vardır. Bu diptik eserinde, bir meteorun sürtünüşüyle dağıttığı küçük parçaları peşinden sürüklemesini ve mutlak bir sessizlikte havada asılı kalmasını izleriz. Sanatçı, litografi taşına anlık çizikler atarak kazır. Yakamozda siyah suyun yüzeyinin yarılması gibi, yankıları etrafına dağılır. Bu yankıların gerçekte de bir sesi vardır; sanatçının, atmosferi olmayan bir gezegene yağan meteorlar gibi taşın üzerine sayısız noktalar yağdırmasıyla taşın yüzeyinde kendine özgü metalik bir yağmur müziği oluşur. Bu vuruşlar, taşın milyonlarca yıllık içinde tuttuklarını sarsarak bize oluştuğu malzemenin geçmişini, dönüşümünü hatırlatır. Karanlığın içinde cam gibi görünen asteroit taş baskısının yapımında ise, taşın üzerine tesadüfi bir leke bırakır ve hava ile dağıtır. Mürekkebin taşta dağılışı, baskıdaki taşın dokusunu oluşturur. Yıldızlara yer verdiği Ma Serisi’nin bir parçası olan bu diptikte sanatçı pratiğinde kullandığı beyaz kâğıt yerini taşa bırakır. Ne tesadüftür ki, Ahmet Doğu İpek’in çocukluğundaki ilk defterleri de taşlar olmuştur.

Fransız litograf Cora Texier, sanat pratiğinde lavis tekniğini kullanır. Lavis tekniği, taşın ıslatılarak mürekkebin tesadüfi dağılışına izin verilmesiyle gerçekleşir. Texier’nin kullandığı bu teknik sayesinde, taş baskılarında dokular önemli bir yer tutarak çoğunlukla doğal malzemelerin taştaki ifadesine dönüşürler. Evinin yakınlarındaki parkta yaptığı yürüyüşlerinde topladığı ağaç kalıntıları, çakıl taşları, bitkiler taş baskılarında yeniden hayat bulur. 2018’den itibaren Paris yakınlarındaki Châtenay-Malabry’deki litografi atölyesinde birçok sanatçıyı ağırlar, onlarla işbirliği yaparak taş baskılar yapar. Bu sergide yer alan eserine, elementlerin ilk oluşum maddesi anlamına gelen Ylem ismini vermiştir. Bu taş baskının ilhamını Kapadokya’daki peri bacalarının oluşumu ve Uçhisar Kalesi’ne yaptığı ziyaretten alır. Sanatçıya göre bu yerler tek bir hakikati ona fısıldarlar: evren, taşlar, yıldız tozu ve hepsini kapsayan maddeyi. Uçhisar Kalesi’ndeki bir mağarada doğal olarak oluşmuş taş biçiminde ve mağaranın derinliklerine bakan bir açıklık fark ederler. Naz Önen’in fotoğrafladığı bu açıklık, sanatçının taşta ifade etmek istediklerine kılavuzluk eder. Texier, litografi taşının üzerinde, lavis tekniğini uygulayarak, mürekkeple koyuluklar ve açıklıklarla oluşturduğu topografyayı andıran alanlarla ona göre zamanda bir geçiş anlamına gelen bu boşluğun, uçurumun bir yorumunu yaratır. Tek bir bütün kâğıdın iki parçasından oluşan taştaki bu leke, rüzgârın ve yağmur suyunun etkisiyle peri bacalarının geçirdiği dönemleri anlatır.

Denizden Çıkan Taşlar sergisi, Dou Print Studio’ya gelen farklı deneyimlere ve sanat pratiklerine sahip sekiz sanatçının milyonlarca yıllık kireç taşı ile buluşmasıyla oluşmuştur. Her sanatçı, atölyede geçirdikleri zaman diliminde, taşın onlara fısıldadıklarını aktarmıştır. Bu sergide ortaya çıkan eserlerin görsel dili, ilk bakışta başkalaşsa da, tek bir taşın kılavuzluğunu derinden taşır. Bir yılın bambaşka zamanlarında, aynı master printer’ın elinden, aynı makinadan ve aynı tür kağıtlara basılarak üretilmişlerdir. Kireç taşının bir zamanlar sular altında, mağaraların, kayalıkların derinliklerindeki yolculuğu, kâğıtta son bulmuştur. Bir insan yaşamı tarafından asla tahayyül edilemeyecek olan taşın kadim zamanından biraz daha geçmiş, taş sanatçıların üretimleriyle biraz daha azalmış, geriye ise sanatçıların onda bıraktığı izler kalmıştır.

* Marcia Bjornerud, Yeryüzünün Zamanı Bir Jeolog Gibi Düşünerek Dünyayı Kurtarabilir Miyiz? Metis Yayınları, 2020.